Ritual, Healing, and Heat: The Cultural Role of Sweat Lodges

Understanding Wendat sweat lodges is essential for accurately representing the Longhouse 6.0 virtual reconstruction. This document provides preliminary research based on archaeological, historical, and linguistic evidence. Following his recent physical reconstruction, Ron Williamson will discuss this in late May, offering further practical insights.

These structures played vital roles in purification, spiritual connection, and social cohesion within Wendat communities, with their forms and functions evolving over time.

Wendat Spiritual Context

The spiritual world was deeply interwoven with the daily lives of the pre-contact Wendat, who believed that souls permeated nearly all aspects of existence, from people and animals to plants and even inanimate objects like rocks (Trigger, 1976). This animistic perspective fostered a profound sense of interconnectedness with the environment. Rituals and ceremonies played a vital role in Wendat society, serving to honour the spirits, ensure the success of hunting and agricultural endeavours, commemorate significant life events, and maintain balance within the community and cosmos (Trigger, 1990 ). While the Wendat may not have had a distinct class of religious specialists akin to shamans in the earliest pre-contact era, chiefs often undertook secular and ritual responsibilities (Trigger, 1976). However, during the 17th century, historical records document Huron individuals with specialized spiritual roles, sometimes referred to as shamans, who utilized sweat lodges, suggesting a complex spiritual landscape. The Wendat observed various feasts (celebratory, thanksgiving, curing, farewell), demonstrating ritual integration into diverse facets of life (Trigger, 1990 ). Purification rites were frequently deemed necessary before significant ceremonies or for maintaining spiritual well-being, preparing individuals for interaction with the spiritual realm. Integrating ritual structures like sweat lodges directly into domestic spaces like longhouses reflects an understanding where ritual and daily life were intertwined, challenging simple sacred/profane dichotomies and aligning with Wendat animistic beliefs where everyday acts could maintain spiritual balance.

Historical Accounts

Early historical accounts from French explorers and Jesuit missionaries provide significant, albeit potentially biased, evidence for sweat-bathing among the Wendat. The Jesuit Relations contain numerous references to Huron sweat lodge use, describing construction, process, and context. These documents distinguish between smaller, possibly temporary lodges used by individuals (particularly shamans) for spiritual purposes and larger structures for communal baths. Gabriel Sagard specifically mentioned Huron constructing sweat lodges both within longhouses and in temporary camps, indicating the practice occurred at household levels and during travel or specific activities (Wrong, 1939 ). While acknowledging the filter of European cultural backgrounds, the consistent mention of sweat bathing strongly implies it was a well-established practice in 17th-century Wendat society.

Linguistic Evidence

Linguistic insights further illuminate Wendat perspectives on sweat bathing. Research by Steckly (1989) into 17th- and 18th-century Huron dictionaries reveals a significant twofold division in terminology. Terms based on the verb root endeon consistently refer to sweat lodges in sacred or spiritual contexts, often involving ceremony and healing. A cognate term in 17th-century Mohawk, Ennejon, reportedly meant both “to sweat” and “to have a feast, ceremony,” suggesting antiquity for the term and its ceremonial association. In contrast, terms not derived from endeon, such as ,arontonta8an (analyzed by Steckly as ‘stones taken out of a fire’) and atiatarihati (‘one heats oneself’), appear to denote profane, non-spiritual, or functional uses, sometimes explicitly described as occurring “without superstition”. This linguistic distinction strongly suggests the Wendat themselves recognized and categorized different contexts and intentions for sweat lodge use, one imbued with spiritual significance and another more secular or functional, even if the physical structure was the same.

Archaeological Evidence

Archaeological evidence confirms the presence of sweat lodges in pre-contact southern Ontario villages, with two main types identified: semisubterranean lodges (SSLs) and post-cluster structures (PCSs).

Connections to Longhouses: Direct physical connections existed. At Coleman, SSL entrances projected through longhouse walls (MacDonald, 1988 ). At Bennett, “pear-shaped” pits (potential SSLs) were exterior or attached via lobate extensions (MacDonald, 1988 ). Access “from beneath” side platforms implies crawl access, not enclosed tunnels.

Types of Sweat Lodges:

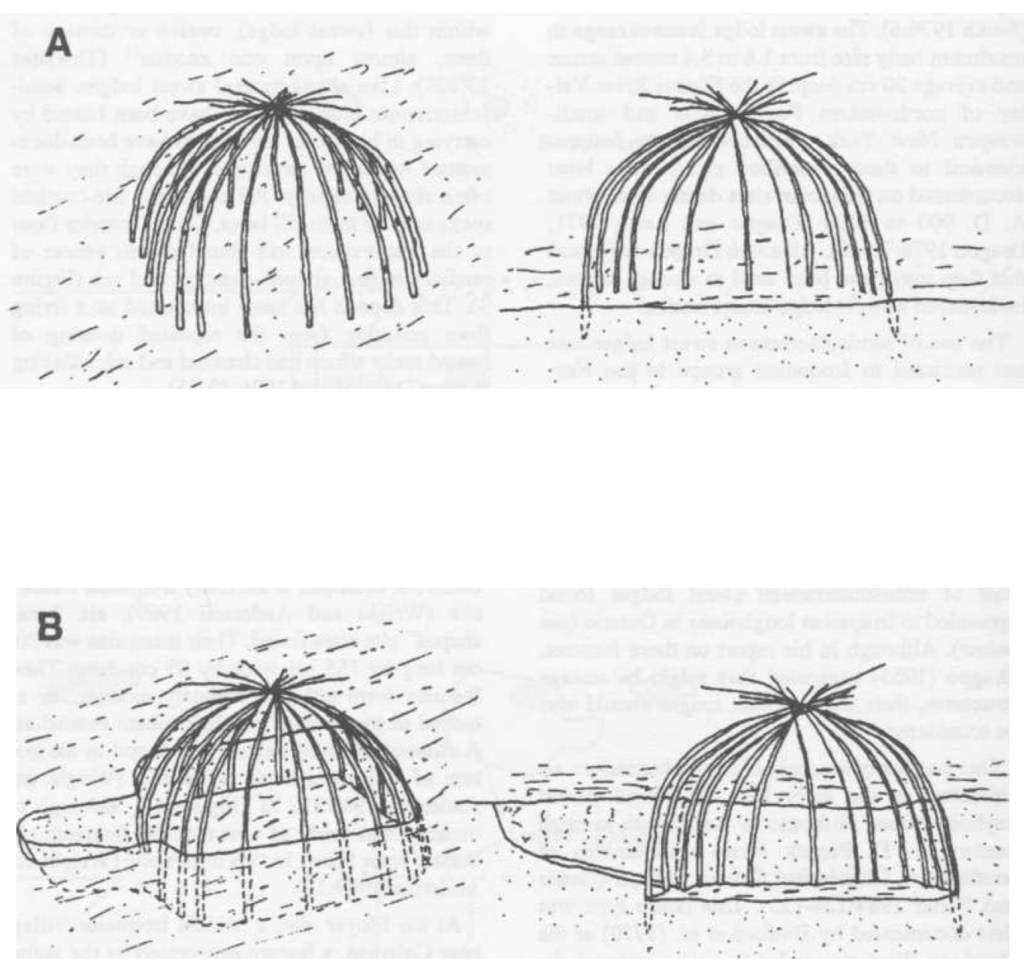

Semisubterranean Lodges (SSLs): Often rectangular (approx. 2×3 meters), dug about 60 cm deep, sometimes with ramped entrances, and covered by superstructures of poles, bark, or hides (MacDonald, 1988 ). Floors could be heavily charred. These features are often characterized by a distinctive “keyhole” or “turtle pit” shape.

Post-Cluster Structures (PCSs): Above-ground structures formed by small circular or oval post clusters, typically found inside longhouses along the central corridor, often behind hearths (MacDonald, 1988 ; Creese, 2011 ; Tyyska, 2015). These are believed to represent temporary structures, matching Sagard’s descriptions. Note: The term “figure-of-eight” was mentioned in the previous draft but could not be confirmed for PCSs in the provided materials.

Identification: Identifying sweat lodge remains presents challenges. Archaeologist Tyyska (1972) hypothesized that many post-mould clusters in longhouse corridors represent temporary, above-ground sweat lodges. Fire-cracked rock and charcoal associated with both PCSs and SSLs support their identification as features involving heat.

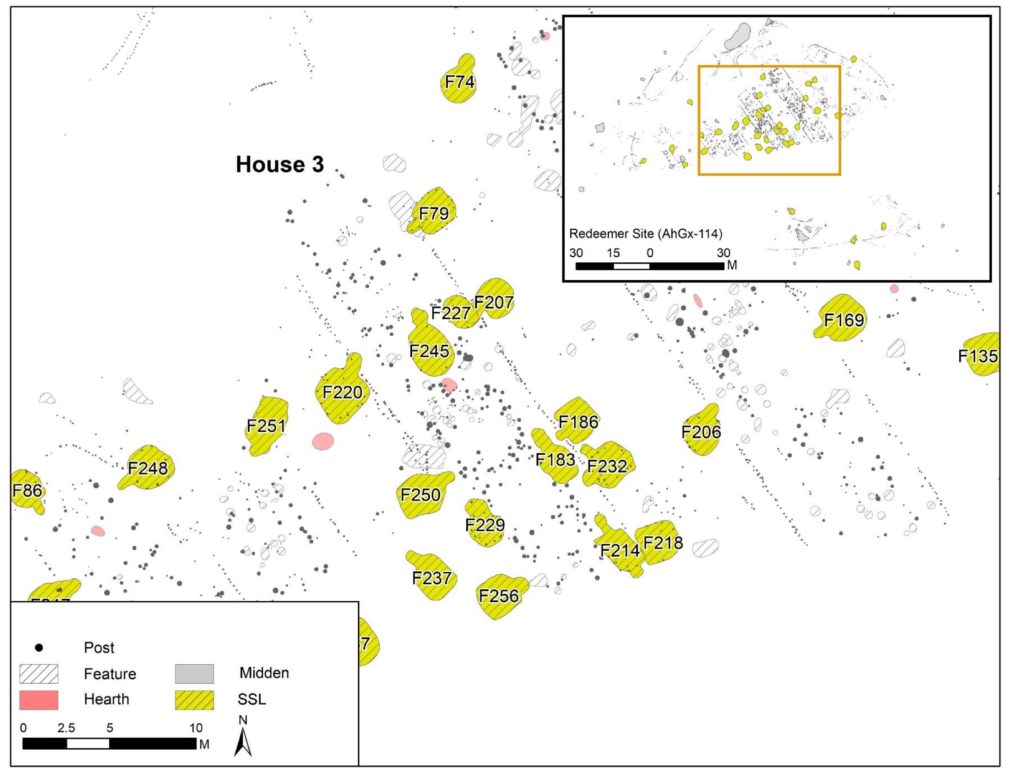

Site Examples: Sites like Draper (PCSs inside longhouses ), Coleman and Bennett (SSLs outside/attached ), Alexandra (lodges near longhouses), Hubbert (high number of SSLs ), and Redeemer (SSLs ) provide evidence. The presence of both types suggests variability in use or chronology. The Hubbert site’s location and features suggest purification practices were important regardless of immediate defensive needs.

Construction: Historical accounts describe above-ground lodges made with bent saplings covered in bark/skins (Wrong, 1939 ). Archaeological PCSs (circular/oval post clusters, ~2m diameter) align with these descriptions. SSLs involved excavating a pit, often with a keyhole shape (and sometimes a ramped entrance), and erecting a superstructure indicated by perimeter post-moulds (MacDonald, 1988 ). The primary method for generating heat involved heating stones in an external fire and carrying them inside, as described in 17th-century accounts by Sagard (Wrong, 1939 ) and corroborated by MacDonald’s (1988 ) analysis of Huron practices. Water was poured on the stones for steam (Wrong, 1939 ). Sagard also noted occasional tobacco burning, hinting at ritual offerings (Wrong, 1939 ). The temporary nature of PCSs contrasts with the more substantial SSLs, potentially indicating different levels of permanence or formality.

Location within the Community and Longhouse:

Semisubterranean Lodges (SSLs): Most (over 80% at Hubbert) were accessed from beneath longhouse side platforms; others were external but accessed similarly, or located in central corridors or end vestibules (MacDonald & Williamson, 2001 ; MacDonald, 1988 ). Orientation varied. This suggests embeddedness within house structures, often concealed, implying control or privacy.

Post-Cluster Structures (PCSs): Consistently found along the central medial line, often behind hearths, suggesting frequent or communal household use (MacDonald, 1988 ; Creese, 2011 ; Tyyska, 2015).

Interpretations of Location: The Draper site’s numerous PCSs inside longhouses suggest household-level practice. Coleman and Bennett’s external/attached SSLs might indicate broader community use. The Hubbert site’s high frequency of SSLs within bunk lines or appended to walls has been interpreted by MacDonald & Williamson (2001) as playing a significant role in fostering social solidarity and maintaining clan cohesion, potentially crucial during periods of village aggregation or social stress.

Significance and Function

The sweat lodge held multifaceted significance. Functions ranged from hygiene to profound spiritual practices. They were used for purification before ceremonies or after specific events. Historical accounts specify shamanic use for contacting the spirit world. Communal baths likely fostered social integration and solidarity. Curative properties were also attributed. Tobacco burning suggests ritual offerings (Wrong, 1939 ). The diverse purposes, also reflected in the distinct linguistic categories identified by Steckly , underscore the lodge’s central role in holistic well-being and maintaining harmony.

Ritual Deposits and Social Integration

Archaeological evidence reveals ritual deposits in SSLs, suggesting symbolic significance. While human remains have been documented in SSLs at other Iroquoian sites (MacDonald, 1992 ; Ramsden et al., 1998; Robertson et al., 1995), the Hubbert site SSLs, according to MacDonald & Williamson (2001), contained symbolic items (like bear skulls and owl wings) but did not yield mortuary remains. Note: Specific evidence from Myers Road (paired SSLs, bear skulls, deer crania) cited to MacDonald et al. (1989) or Creese (2011) requires verification from the original sources. Paired SSLs suggest coordination between social units. The Hubbert site’s 17 SSLs showed coordinated realignment reinforcing longhouse symmetry. The appearance of temporary sweat baths (PCSs) within longhouses, potentially linked chronologically by Tyyska (2015) to the emergence of communal ossuaries, may represent another powerful social integrative mechanism crucial during periods of community redefinition and stress. By the 17th century, ethnographic descriptions align well with the archaeological PCSs, suggesting cultural continuity or transformation.

Conclusion

Archaeological, historical, and linguistic evidence confirms the significant and multifaceted role of sweat lodges in pre-contact Wendake communities. Found in both domestic and potentially communal spaces, they served purposes extending from physical cleansing to profound spiritual and social functions, reflecting the holistic Wendat worldview. The convergence of evidence—distinct archaeological forms (SSLs, PCSs), varied locations, historical accounts of diverse uses, and specific linguistic categories differentiating sacred and profane contexts 4—paints a picture of a dynamic institution central to Wendat life. The integration of lodges into village life underscores their importance, potentially evolving in form (from more permanent SSLs possibly emphasized earlier to temporary PCSs described historically 38) and function to meet the changing needs of Wendat society, particularly in fostering social cohesion and navigating spiritual relationships.5 While this synthesis integrates diverse evidence, acknowledging methodological limitations, such as potentially restricted access to some foundational debate texts (e.g., Bursey 1989 49, Stopp 1989 73), is important. Future research focusing on micro-analysis within features and broader comparative studies, considering Wendat agency in adapting these ritual practices, will continue to enrich our understanding of this vital aspect of their culture.

Table 1: Archaeological Evidence of Sweat Lodges at Selected Wendat Sites

| Site Name | Type of Sweat Lodge | Location within Village | Key Characteristics | Citations |

| Alexandra Site | Unknown | Within the village | Evidence of sweat lodges found alongside longhouses and garbage pits | (ASI, 2008 report cited in 44; Lajeunesse, 2016; Creese, 2011 35) Note: Citations require verification/completion. |

| Draper Site | Above-Ground (PCSs) | Inside Longhouse (central corridor) | Circular clusters of post-moulds, approx. 2 meters in diameter | (MacDonald, 1988 32; Creese, 2011 35) |

| Coleman Site | Semisubterranean (SSLs) | Outside Longhouse (attached) | Keyhole shape, ramped entrance projecting through longhouse wall, perimeter posts | (MacDonald, 1988 32; Creese, 2011 35) |

| Bennett Site | Semisubterranean (SSLs) | Outside/Attached to Longhouse | Pear-shaped pits, some attached via lobate extensions | (MacDonald, 1988 32; Creese, 2011 35) |

| Hubbert Site | Semisubterranean (SSLs) & PCSs | Within & Appended to Longhouses | 17 SSLs; symbolic items (bear skulls, owl wings); no human remains reported | (MacDonald & Williamson, 2001 5; Creese, 2011 35) |

| Redeemer Site | Semisubterranean (SSLs) | Within village | SSLs identified at a 14th-century Iroquoian village; standardized construction; artifact deposition | (Parks, 2018 48; Creese, 2011 35) |

| Myers Road | Semisubterranean (SSLs) | Inside Longhouse | Paired SSLs flanking central hearth, ritual deposits | (Creese, 2011 33; MacDonald et al. 1989 56) Note: Specific deposit details require verification. |

Table 2: Historical Descriptions of Wendat Sweat Lodges

| Source | Date of Account | Description of Sweat Lodge | Citations |

| Sagard | 1623-24 | Dome-shaped frame of sticks, covered with bark/skins; heating with hot stones; communal use; inside longhouses & camps; tobacco sometimes burned | (Wrong, 1939 22; MacDonald, 1988 32) |

| Jesuit Relations (Lalemant) | 1639 | Small, temporary structures; heating with hot stones; individual use by shamans | (MacDonald, 1988 32; Jesuit Relations 4) |

| Jesuit Relations (Various) | 1634-1650 | Communal sweat baths; periodic breaks; singing/chanting; tobacco sometimes burned | (MacDonald, 1988 32; Jesuit Relations 6) |

Table 3: Linguistic Terms for Sweat Lodges in Huron (Based on Steckly 1989 4)

| Huron Term | Literal Translation (if available) | Context of Use | Key Insights |

| endeon | Sacred/Spiritual (with ceremony) | Linked to ceremony, healing, spiritual specialists; cognate in Mohawk. | |

| ,arontonta8an | Stones taken out of a fire | Profane/Secular (without superstition) | Refers to the heat source; used without ceremony or superstition. |

| atiatarihati | One heats oneself | Profane/Secular | Indicates a non-spiritual use focused on personal heating or hygiene. |

Works Cited

Note: This list includes sources cited in the text and tables based on available information. Some sources mentioned (Lajeunesse 2016, Robertson et al. 1995, Tyyska 1972, Bursey 1989, Stopp 1989) require full bibliographic details and verification. Irrelevant citations (Hodder, OHRC, Pluralism Project) have been removed. The ASI citation needs clarification if referring to a specific Alexandra site report.

Creese, J. L. (2011). Ancestral Iroquoian Houses: A Case Study in Archaeological Method and Theory (Doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto). 35

Jesuit Relations (1634–1650). Various accounts. In R. G. Thwaites (Ed.), The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents (Vols. 1-73). Burrows Brothers. (Accessible online via Creighton University 11 and Early Canadiana Online 12)

MacDonald, R. I. (1988). Ontario Iroquoian Sweat Lodges. Ontario Archaeology, 48, 17–26. 4

MacDonald, R. I. (1992). Ontario Iroquoian semisubterranean sweat lodges. In A. S. Goldsmith, S. Garvie, D. Selin, & J. Smith (Eds.), Ancient Images, Ancient Thought: The Archaeology of Ideology (pp. 343-349). Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Chacmool Conference, University of Calgary Archaeological Association. 48

MacDonald, R. I., Ramsden, C., & Williamson, R. F. (1989). The Myers Road site: shedding new light on regional diversity in settlement patterns. Canadian Journal of Archaeology, 13, 207-211. 56

MacDonald, R. I., & Williamson, R. F. (2001). Sweat Lodges and Solidarity: The Archaeology of the Hubbert Site. Ontario Archaeology, 71, 29-78. 5

Parks, A. (2018). The Semi-Subterranean Sweat Lodges of the Redeemer Site (Master’s thesis, The University of Western Ontario). 48

Ramsden, P. G., Robertson, D. A., & Smith, B. A. (1998). Mortuary Practices at the Cameron Site. Ontario Archaeology, 65/66, 88–104. 9

Steckly, J. (1989). Huron Sweat Lodges: The Linguistic Evidence. Arch Notes, 89(2), 17–21. 4

Trigger, B. G. (1976). The Children of Aataentsic: A History of the Huron People to 1660 (Vols. 1-2). McGill-Queen’s University Press. 9

Trigger, B. G. (1990). The Huron: Farmers of the North (Case Studies in Cultural Anthropology). Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Tyyska, A. (2015). Huron-Wendat sweat baths. Ontario Archaeology, 95, 64-78. 38

Williamson, R.F. (1990). Mortuary Practices and the Role of the Spirit World in Northern Iroquoian Societies. In C.J. Ellis & N. Ferris (Eds.), The Archaeology of Southern Ontario to A.D. 1650 (pp. 289–306). London Chapter, Ontario Archaeological Society.Wrong, G. M. (Ed.). (1939). Sagard’s Long Journey to the Country of the Hurons (H. H. Langton, Trans.). The Champlain Society. (Original work published 1632) 22